Modern Context Engineering

The effectiveness of large language models is directly tied to the quality of the prompts they are given. In December 2022, the term prompt engineering gained popularity as a way of describing effective prompting strategies that produce high quality and relevant LLM outputs. Now, in 2025, the term context engineering has gained popularity alongside the rise of LLM agents and agentic systems.

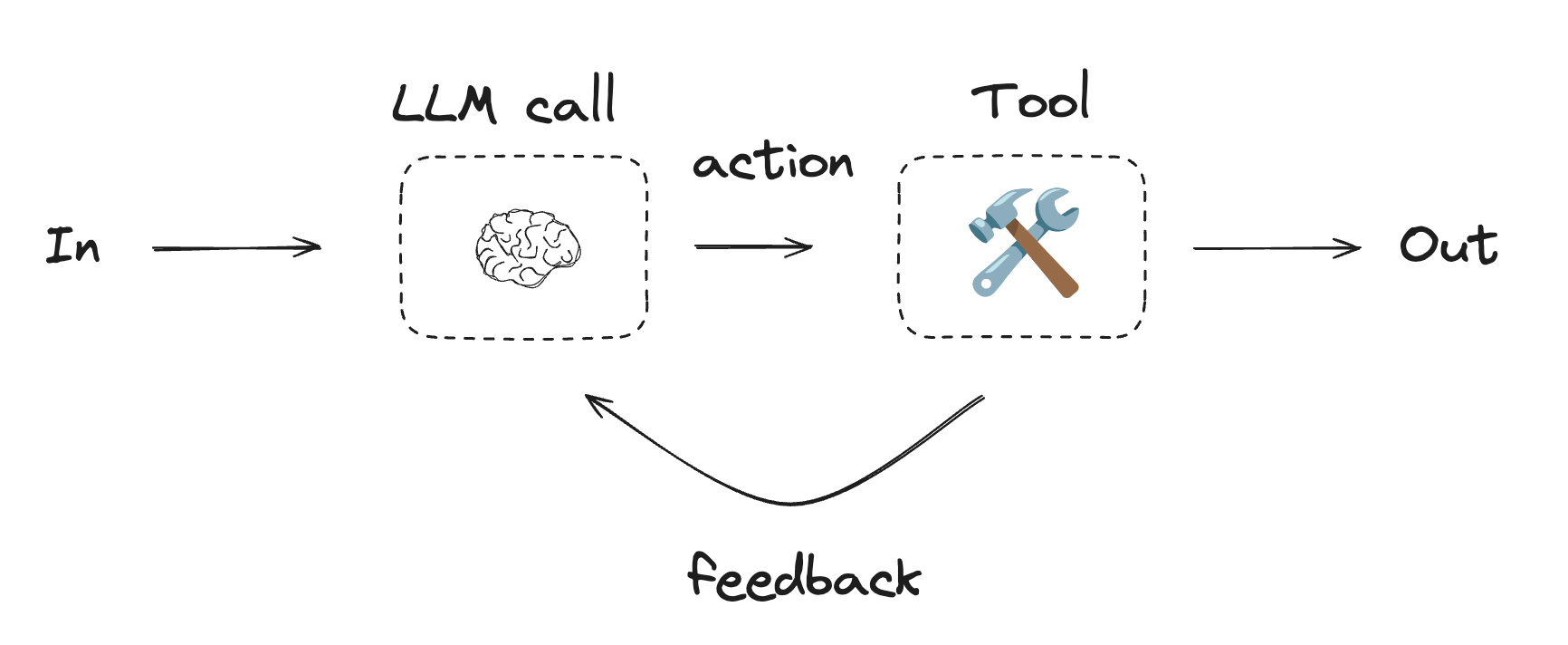

To understand context engineering we must first understand what an agent is. The most primitive form of an agent is the ReAct agent. The term ReAct comes from the Reasoning and Action loop these agents use to accomplish a given objective.

Given a certain goal and an array of tools to use, the LLM decides an action to take and calls a tool to do it. The results of these tool calls are observed and fed back to LLM to decide whether further action should be taken (continue the loop) or if the given goal has been accomplished (end the loop). You can think of the LLM as the agent’s brain and the tools as its body - allowing it to interact with its environment.

https://langchain-ai.github.io/langgraph/tutorials/workflows

https://langchain-ai.github.io/langgraph/tutorials/workflows

In order for an agent to make a decision, it needs a prompt/context. That prompt/context is stored inside the LLM’s context window. As the LLM makes more decisions and calls more tools, it stores previous tool calls and decisions inside the input context window. As you can imagine, agents running over longer periods of time start to generate and store a significant amount of context. Although context windows have been getting larger (with some models supporting over 1M tokens of context), agents suffer from both performance degradation and increased cost of inference when dealing with large input context.

The term context engineering gained popularity in May 2025 - coinciding with the rise in popularity of agentic systems. Andrej Karpathy describes it best as “the delicate art of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.”

https://x.com/karpathy/status/1937902205765607626

In this post, we’ll be discussing why context engineering is important and some new techniques developers are using to effectively manage context windows in agentic systems.

This post is a summary of a recent webinar hosted by Lance Martin (Founding Engineer @ LangChain) and Yichao “Peak” Ji (Co-Founder + Chief Scientist @ Manus) titled Context Engineering for AI Agents with LangChain and Manus.

Table of Contents

- Why Context Engineering?

- 5 Pillars of Context Engineering

- Cache

- Offload

- Offloading Tools: Hierarchical Action Space

- Function Calling

- Sandbox Utilities

- Packages & APIs

- Offloading Tools: Hierarchical Action Space

- Reduce

- Isolate

- Retrieve

- Final Thoughts

- Resources

Why Context Engineering?

When developers first started building agentic systems a consistent phenomena emerged - the longer an agent would run, the more context needed to be stored. In these systems we have an LLM bound to some number of tools that the LLM can call autonomously in a loop. The challenge is that for every decision made and tool call observed, the LLM’s messages and tool call observations are appended to a chat list as context. These messages grow over time and you end up with an unbounded explosion of messages as the agent runs. To put this in perspective, Manus' general-purpose AI agent requires around 50 tool calls per task. Anthropic agents often engage in conversations spanning hundreds of turns. So you can imagine the scale of context that needs to be managed in order for these systems to run effectively.

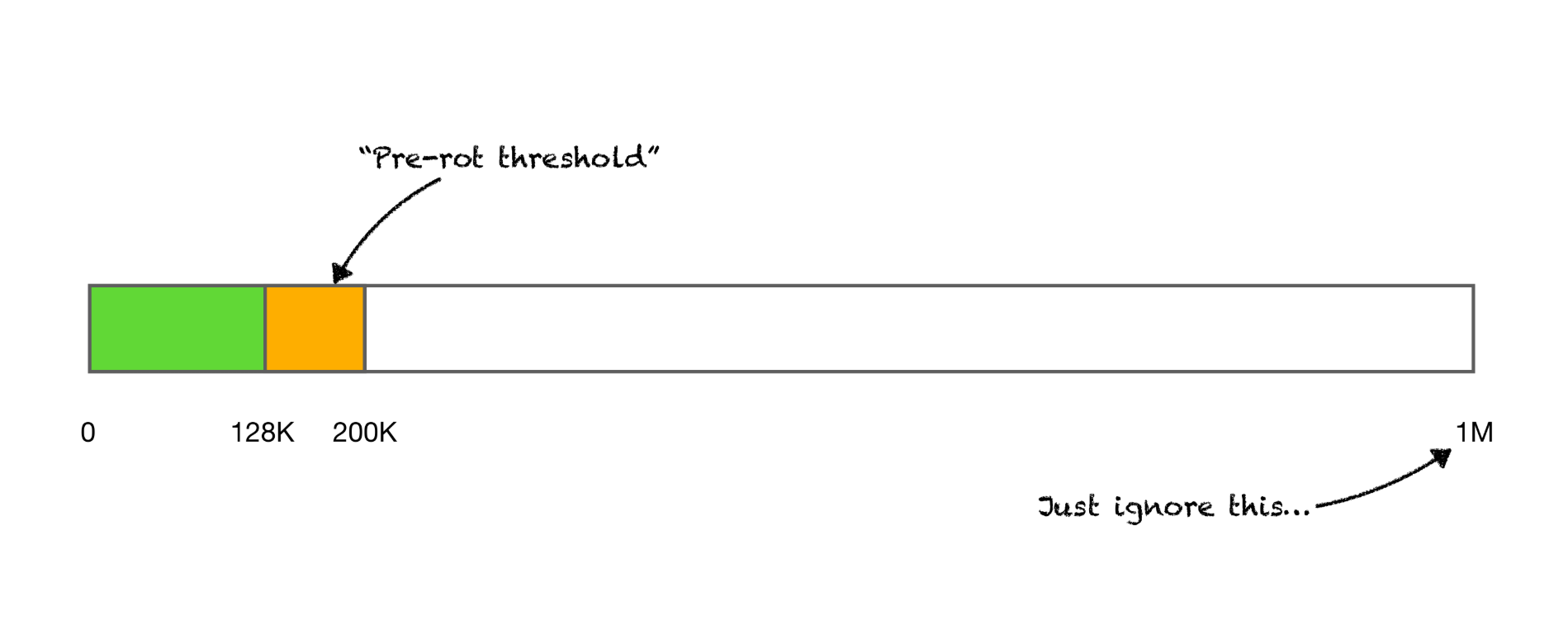

As the context grows, performance drops. This is referred to as context rot. Many modern models have context windows up to 1M tokens but the reality is most models start degrading at around 200k tokens. Researchers at Chroma made a great blog post about this phenomenon which I highly recommend. At a high level - context rot leads to repetitions, slower inferences, lower quality, and increased inference cost.

Now, let’s explore the ideology behind context engineering so we can avoid context rot. We’ll also focus on some new techniques for context engineering being implemented by the Manus team in their general-purpose AI agent.

5 Pillars of Context Engineering

The paradox: agents need a lot of context to perform well, but performance drops as context grows.

The solution to this is context engineering - which is made up of five main pillars: Cache, Offload, Reduce, Isolate, and Retrieve.

Cache

First, we need to understand caching as it applies to LLMs. KV-caching refers to the practice of caching the key and value state of generative transformers. By caching the previous keys and values, the model can focus on only calculating the attention values for new tokens. It is important to design your agentic system around the KV-cache. Doing so decreases the computation (and cost) needed for inference while also decreasing time-to-first-token.

A few key practices to improving KV-cache hit rate include keeping your prompt prefix stable, making your context append-only, and marking cache breakpoints explicitly when needed. You can read more about this in Manus' blog post on context engineering from a few months ago (highly recommend).

Offload

Offloading context is essential to effective context engineering. You don’t need all context to live in the context window of your agents, you can offload it and retrieve it later. The most common way to do this is by using a filesystem. Take the output of a tool call or message, dump it to the filesystem, and send back some minimal piece of info to your agent so it can access the full context if it needs to. This allows you to avoid stuffing token-heavy context into your context window unnecessarily. Filesystems are typically used for planning, long-term memories, and other token-heavy context.

Tool definitions typically sit at the beginning of your context so the LLM knows which tools are available for use at runtime. As the system grows, you’ll find that the tools themselves can often take up a lot of context. Having too many tools in context can lead to confusion for the LLM on which tool to call. The model may call the wrong tools or even nonexistent ones. Offloading tools is another way to improve agent performance.

A common approach to offloading tools right now is doing a dynamic RAG on tool descriptions - loading and removing tools on demand depending on the current task. However, this causes two main issues. First, since tool definitions sit at the front of your context, the KV-cache resets every time. Second, the model’s past calls to remove tools are still in the context, so it might few-shot the model into calling invalid tools or using invalid parameters.

Offloading Tools: Hierarchical Action Space

To solve this, Manus is experimenting with a layered action space. They essentially allow the agent to choose between three different levels of abstraction: function calling, sandbox utilities, and packages & APIs.

Function Calling

This is the classic function calling everyone is familiar with in agentic development. The key difference is that Manus only uses 10-20 atomic functions. These are functions like reading/writing files, executing shell commands, searching the internet, browser operations, etc. These atomic functions have very clear boundaries which leads to less confusion when the LLM is deciding which tools to call. They can also be chained together to compose much more complex workflows.

Sandbox Utilities

Each Manus session runs inside a full VM sandbox - a throwaway Linux container preloaded with custom tooling. This allows Manus to take advantage of everything Linux has to offer without overloading the context window - you can add new capabilities without touching the model’s function calling space. The agent knows that all the tools it can use in this environment are located in /usr/bin and that it can use the --help flag for context on how to use a tool. For large outputs, the agent can write to files or return the results in pages and use Linux command line tools like grep, cat,less, and more to process those results on the fly.

Packages & APIs

Manus can write python scripts to call pre-authorized APIs or custom packages. This is perfect for tasks that require lots of computation in memory but don’t require all the context to be pushed into the context window. For example, if you’re analyzing stock data over the course of a year. You don’t need to push all the price data into the context window, you just need to write a script to pull data from a stocks API, analyze it, and return a summary back to context.

By using this kind of hierarchical action space, you don’t add any overhead to the model. From the model’s POV, all three levels still go through the same standard atomic function calls, allowing you to balance capability, cost, and cache stability.

Reduce

Reducing context is exactly what it sounds like, shortening information without losing important context. This can be by reducing tool call outputs, reducing message outputs, or pruning old tool calls and unnecessary context.

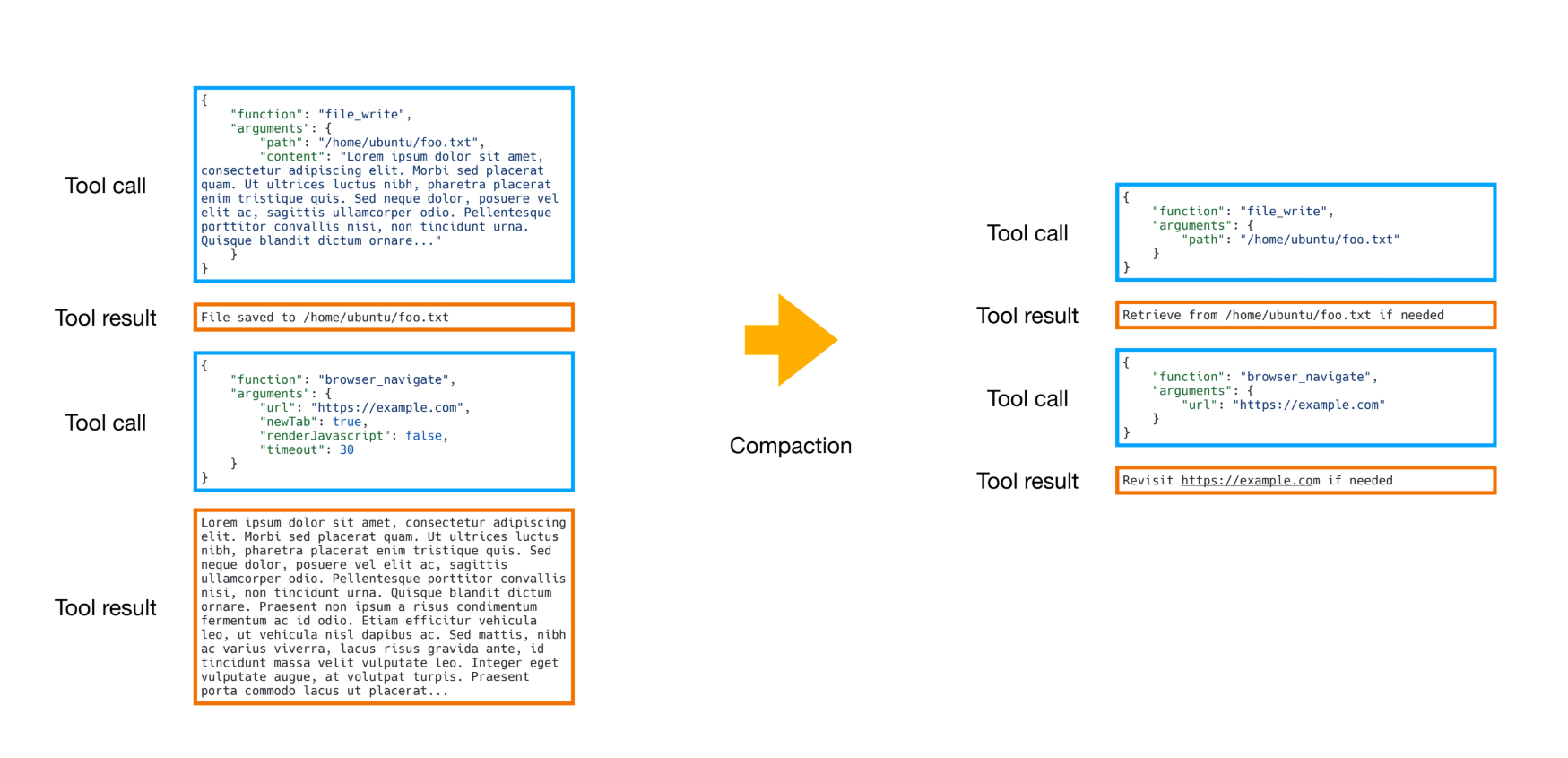

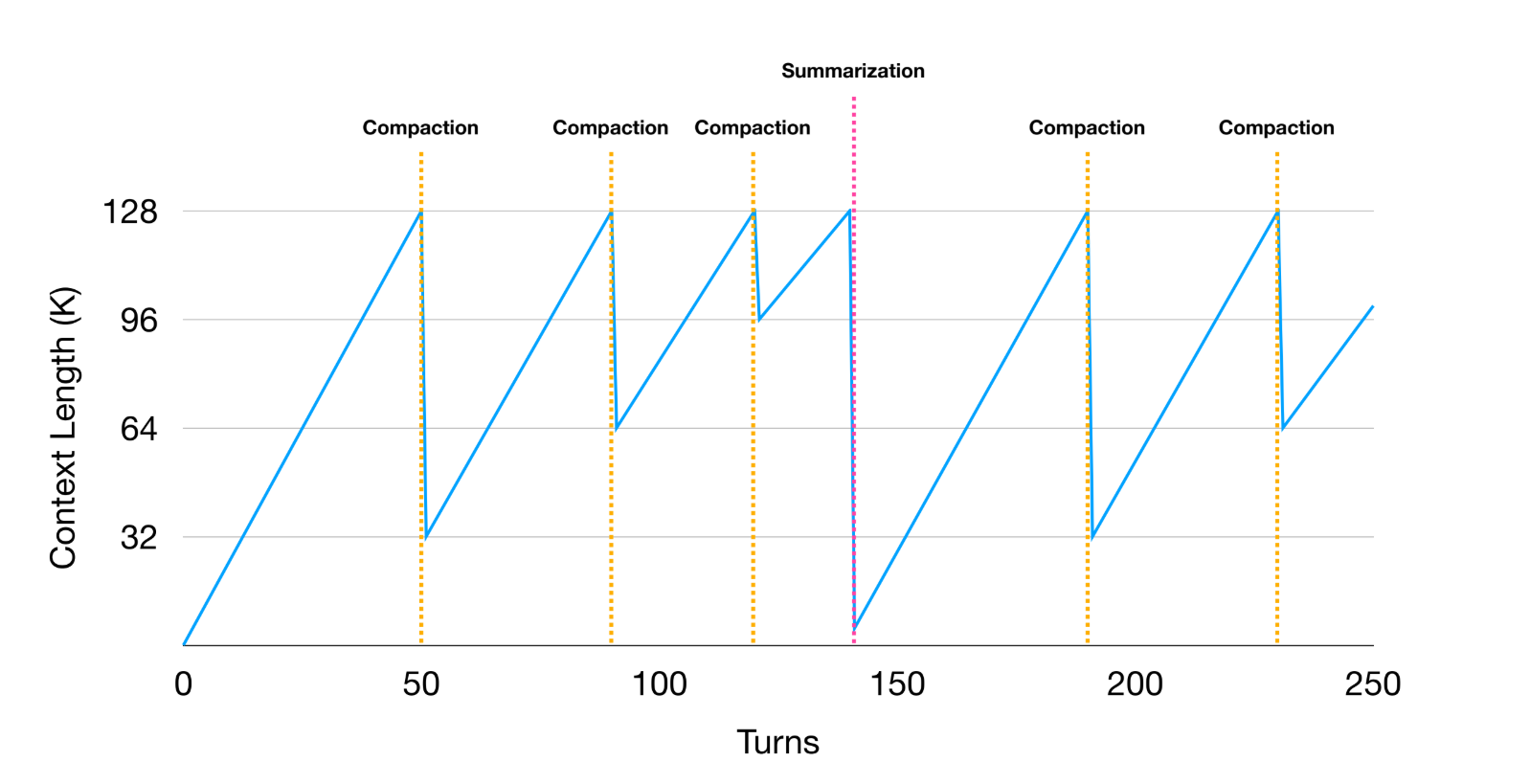

Manus divides reduction into two parts: compaction and summarization.

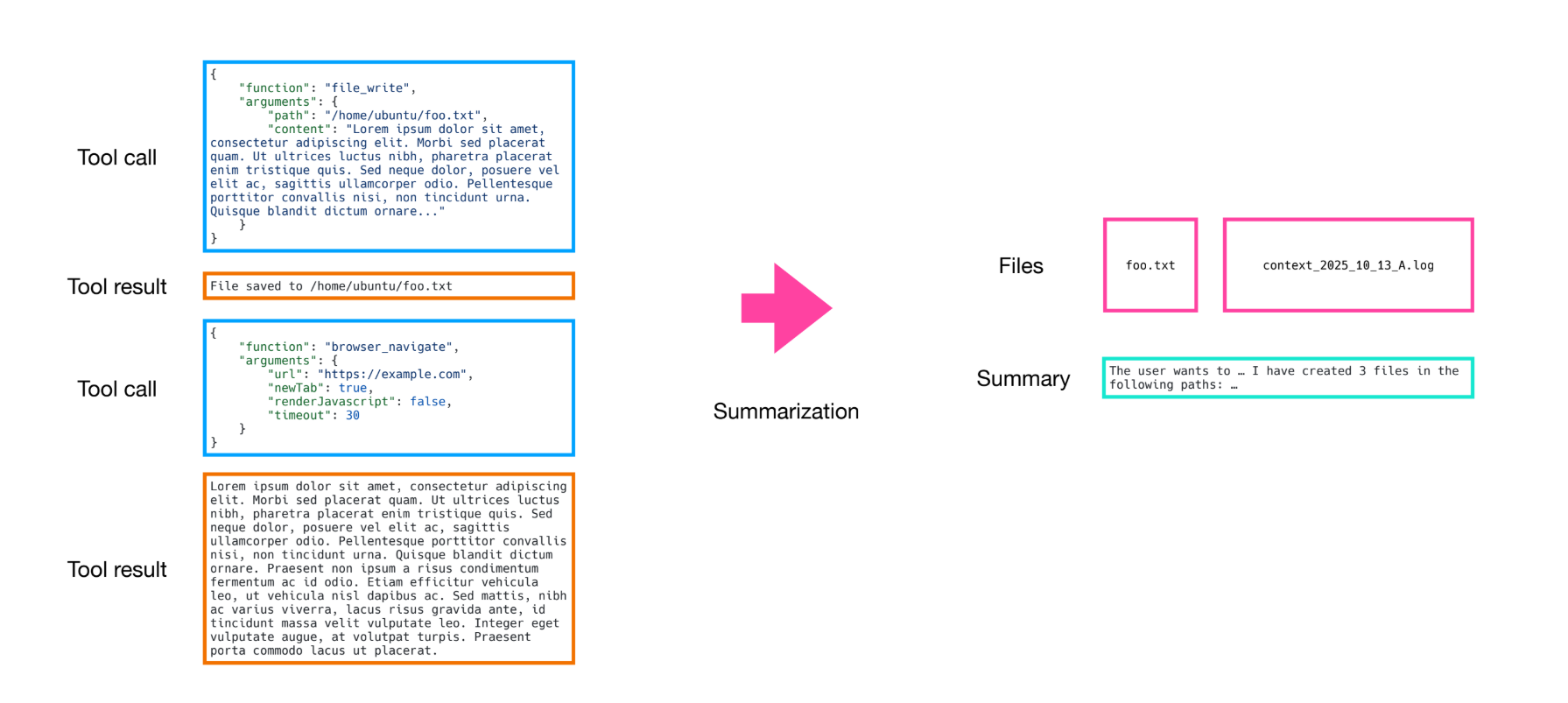

In Manus every tool call and tool result has two different formats - full and compact. The compact format strips out any information that can be reconstructed from the filesystem or external state. For example, say you have a tool that writes to a file. It most likely has two input parameters - one for a path to the file and one for the content to be written. Once the tool returns, we can assume the file already exists in the environment so we can drop the token-heavy content field in the compact format and just keep the path to the file. If the agent needs to read that file again, it can retrieve it via the path so no information is truly lost - only externalized. This kind of reversibility is crucial because agents chain predictions based on previous actions and observations. You never know which past action will suddenly become important context for the next step, so in the event you need the full context - it’s available.

Compaction will only get your so far, your context will continue to grow and eventually hit the ceiling, that’s where summarization comes in.

Manus combines compaction with summarization very carefully. The key difference between compaction and summarization is that compaction is reversible, summarization is not. Both reduce context length but do so very differently. In some cases it can be advantageous to dump the entirety of the pre-summary context as a text file or log file into the filesystem so it’s always recoverable later. You can prompt your agent to look for the full context on demand using Linux tools like glob and grep. Manus tried various ways to optimize the prompt for summarization but it turns out the simple approach works best. You don’t use a free form prompt to let the LLM generate a summary. Instead, you use structured outputs to define a schema/form with fields indicating required points of summarization, then allow the LLM to modify those fields. This enforces that key points are always summarized and allows you to have a somewhat stable output you can iterate off of.

In order to implement both methods effectively, developers must track some context length thresholds. In order to avoid context rot it’s important to identify a pre-rot threshold (typically around 128k to 200k tokens) that triggers context reduction.

Whenever your overall context size approaches this threshold, you start with compaction NOT summarization. Compaction should start with the oldest context in the message history. For example, we might compact the oldest 50% of tool calls while keeping the newer ones in full detail so the model still has some fresh full-shot examples of how to use tools properly.

Whenever your overall context size approaches this threshold, you start with compaction NOT summarization. Compaction should start with the oldest context in the message history. For example, we might compact the oldest 50% of tool calls while keeping the newer ones in full detail so the model still has some fresh full-shot examples of how to use tools properly.

When compaction is triggered, we need to check how much free context we obtained through the operations. After multiple rounds of compaction, if we are still nearing our threshold, we start summarizing.

A tip for summarization: always use the full version of the data and not the compact one. Also, keep the last few tool calls and tool results in full detail because it allows the model to know where it left off and to continue smoothly.

Isolate

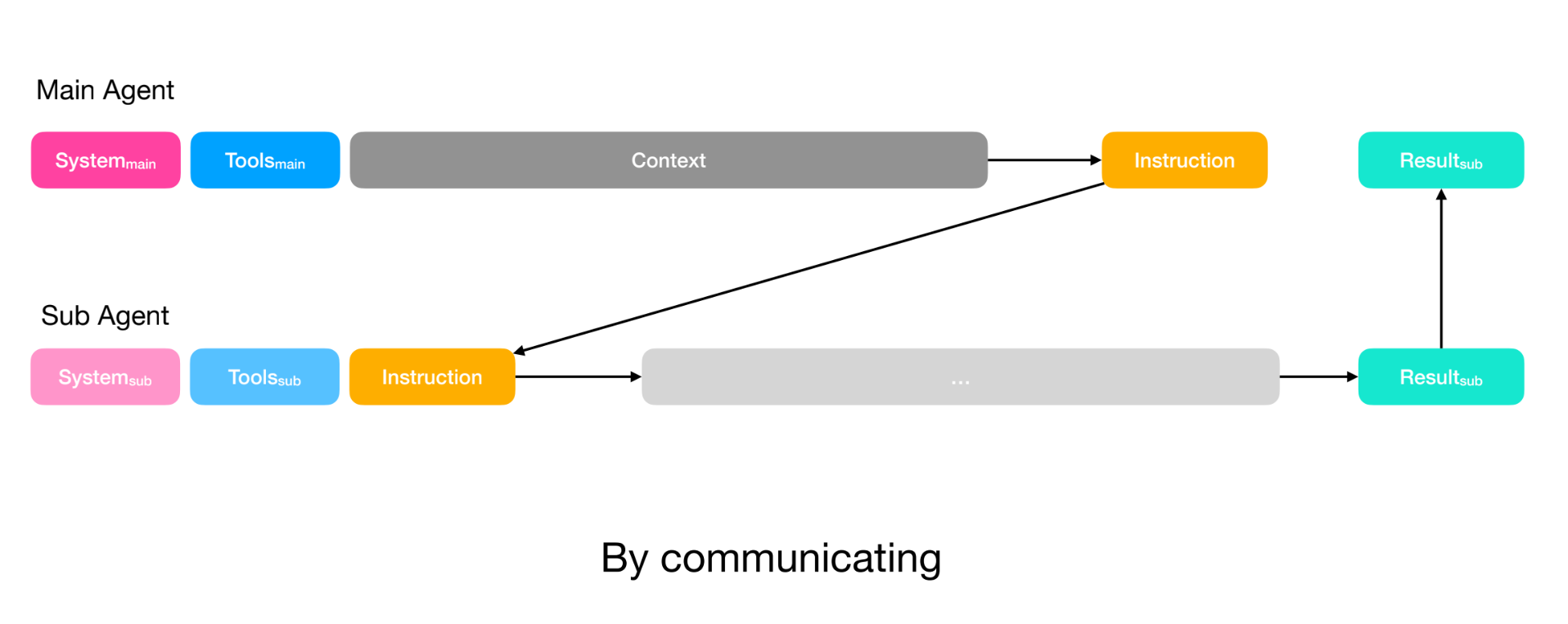

Isolating context is all about issuing relevant context to the context windows of relevant sub-agents. Each sub-agent has its own context window, so we can leverage them to accomplish certain aspects of the overall task whilst keeping their context window limited to the information they need to complete their task. This allows for a separation of concerns within the system, ensuring each agent is not burdened by unnecessary context.

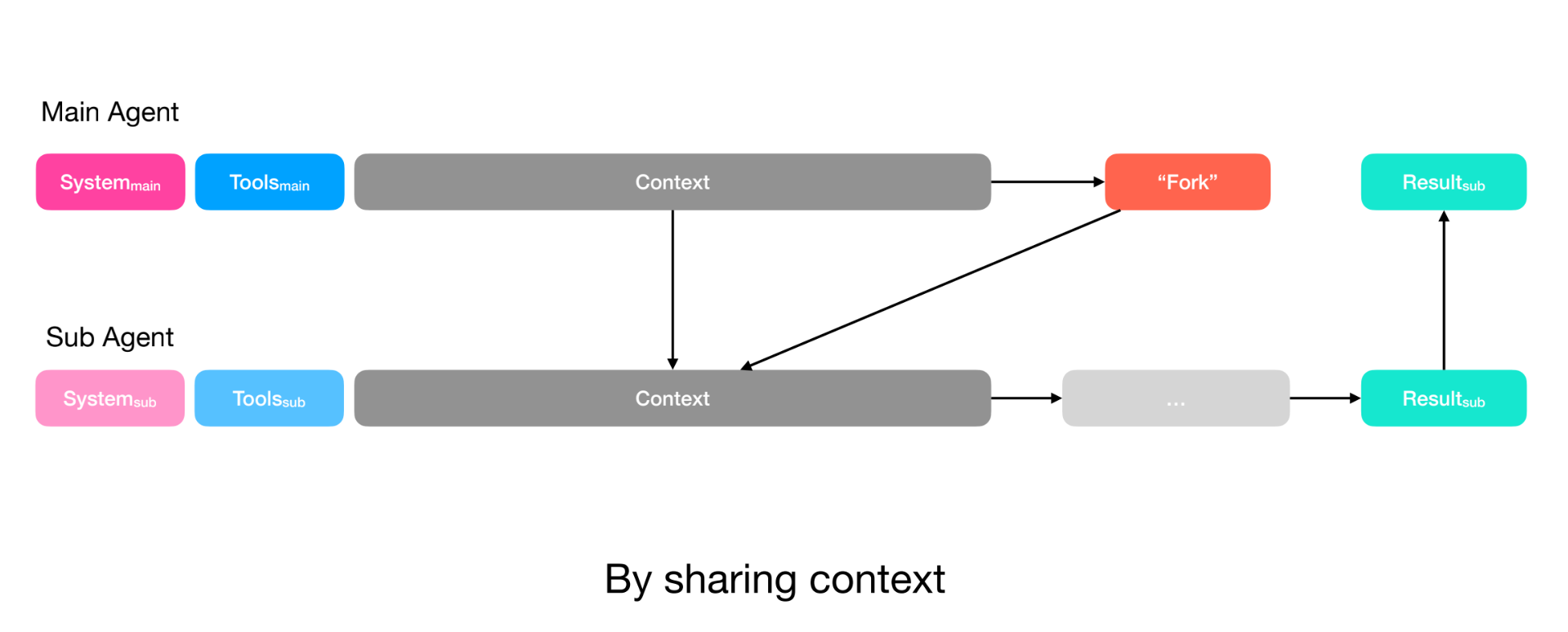

Manus considers context isolation in two different patterns: sharing context by communication, and communication by sharing context.

Sharing context by communication is the easier pattern to understand, it’s the classic sub-agent setup.

The main agent writes a prompt and sends it to a sub-agent. The sub-agent’s entire context only consists of that instruction prompt. This is ideal if the task has a short/clear instruction and only the final output matters, like searching a codebase for a specific snippet. The result is then returned to the main agent.

For more complex scenarios, it may be advantageous for the sub-agent to see the entirety of the previous context. This is the communication by sharing context pattern. The sub-agent has access to all of the main agent’s context, but has it’s own system prompt and it’s own tools. For example, imagine a deep-research scenario. The final reports depends on a lot of intermediate searches and notes. In that case you would use this pattern to share all those notes and searches. If you were to force the agent to re-read all of those contexts by retrieving from the filesystem, you’re wasting latency and context.

Be aware that sharing context is expensive, each sub-agent has a larger input to pre-fill. You’ll end up spending more on input tokens, and because both the action space and system prompt differ, you cannot reuse the KV-cache.

Retrieve

We touched on retrieval earlier, the best method is highly debatable and really comes down to what works best for you in your implementation. The two most popular methods for context retrieval are semantic search and filesystem search. The former is a RAG type system using a vector database and semantic search for retrieval. The other is using a file system with file search tools like glob and grep to retrieve relevant context. A combination of both can be advantageous in certain scenarios.

Final Thoughts

A few things to consider.

Building agentic systems is barely a year old, the rules of engagement are constantly changing. What’s considered best practice now may not hold true in a few months. Staying on top of emerging trends and new advancements allows your system to evolve and improve.

The five pillars are not independent, they enable and compliment each other. Offload + retrieve enables more efficient reduction, stable retrieve makes isolation safe, isolation reduces the frequency of reduction, and more isolation + reduction impacts cache efficiency and the quality of output.

Avoid context over-engineering. The biggest leaps Manus has achieved haven’t come from adding more fancy context management layers or clever retrieval hacks. They all came from simplification and removal of unnecessary tricks. Every time they simplified the architecture and trusted the model more, the system got faster, more stable, and smarter. The goal of context engineering is to make the model’s job simpler, not harder.

Resources

Original Webinar - Youtube

Lance’s Slides - Google Docs

Peak’s Slides - Google Drive

Context Engineering for Agents - A comprehensive guide on write, select, compress, and isolate strategies

The Rise of “Context Engineering” - Understanding why context engineering is the most important skill for AI engineers

Context Engineering in Agents (Docs) - Technical documentation on implementing context engineering with LangChain

Deep Agents - How planning, sub-agents, and file systems enable complex agent tasks

GitHub: Context Engineering Examples - Hands-on notebooks covering all four context engineering strategies